Matthew Lindfield Seager

Event Sourcing Made Simple was pretty persuasive about the benefits of decoupling the model from the events in an app that cause the model to be changed.

Piotr Solnica then reinforced those ideas on Remote Ruby

I love the idea of No Backlog. If an idea has merit but misses a cycle, someone can track it individually and re-raise it later.

I‘ve found backlogs to be burdensome… plus it’s all too tempting to pity-pick a project just because its been waiting on the backlog a long time!

Modules as Classes in Ruby

Today I learned that Ruby modules are actually implemented as classes under the hood.

When you include a module (which is kind of a class in disguise), it actually gets dynamically inserted into the inheritance tree.

Consider the example of a school. We might have a Person class to model every person in the school with some common attributes:

class Person

attr_accessor :given_name

attr_accessor :surname

end

Then we might have subclasses for students, staff and parents to model attributes specific to each group. Focusing on the student, our program might look like this:

class Person

attr_accessor :given_name

attr_accessor :surname

end

class Student < Person

attr_accessor :year_level

end

To add attributes to staff and students that don’t apply to parents we could define a module and mix it in. Let’s say we want to be able to add students (e.g. Harry and Ron) and staff (e.g. Minerva McGonagall) to a house (e.g. Gryffindor). Our program now looks more like this:

class Person

attr_accessor :given_name

attr_accessor :surname

end

module House

attr_accessor :name

attr_accessor :colour

end

class Student < Person

include House

attr_accessor :year_level

end

Previously Student inherited directly from Person but now the House module (or, more accurately, a copy of it) gets inserted as the new parent class of Student. Under the hood the inheritance hierarchy now looks more like Student < House < Person.

That’s all well and good but Ruby doesn’t support multiple inheritance; each class can only have one parent. So how does including multiple modules work? It turns out, they each get dynamically inserted into the inheritance tree, one after another.

Stretching our example a little further, if we had some attributes common to parents and students, we might use another module. Perhaps we want to record the household so we can model that Ron, Ginny and Mr & Mrs Weasley are all part of the “Weasley” household (I’m stretching this example quite far, hopefully it doesn’t snap and take out an eye). Our student class might now look like this:

class Person

attr_accessor :given_name

attr_accessor :surname

end

module House

attr_accessor :house_name

attr_accessor :house_colour

end

module Household

attr_accessor :household_name

attr_accessor :address

end

class Student < Person

include House

include Household

attr_accessor :year_level

end

Under the hood, Ruby first inserts House as the new parent (superclass) of Student but then on the very next line it inserts Household as the parent of Student. The inheritance chain is now Student < Household < House < Person.

There’s always several things worth reading in the Ruby Weekly newsletter

So far this week I’ve enjoyed reading about the regexp-examples gem (and Tom Lord’s associated blog post)

🎉 Free ebook with hard cover purchase

😐 Fine print says 45 days “free access”

😞 They cancelled that program… now it’s 30 days

🤦♂️ The “30 days free” link takes you to a 10 day free trial

“I am altering the deal. Pray I don’t alter it any further.” – Big Publishers

📚 🎧 Finished listening to 9 Perfect Strangers - www.goodreads.com/book/show…

First time I’ve read Liane Moriarty; thoroughly enjoyed it! Some laugh out loud moments but in the end she made me care about every single (flawed!) character!

This evening my son and I switched to Codenvy.com for his school project (he is building a quiz app).

It’s a bit more complicated to get going than repl.it and came with much older software versions but it seems to have a much higher ceiling and less weird constraints.

It feels similar to where Cloud9 used to be… before Amazon bought it and “AWSed” (complicated) it.

Today I finished going through the StimulusJS handbook and examples; stimulusjs.org/handbook/…

I haven’t used it in a proper Rails project yet but I’m sold on the principles.

I think I might need to learn ActionCable too though.

The good, the bad & the surprising of repl.it/languages/rails (after 2nd session with my 9 year old):

✅ WAY easier to get going than homebrew, rbenv, Ruby, bundler, Rails gems, etc

❎ Issues submitting forms due to invalid CSRF tokens

✳️ Database (SQLite) wasn’t persisted

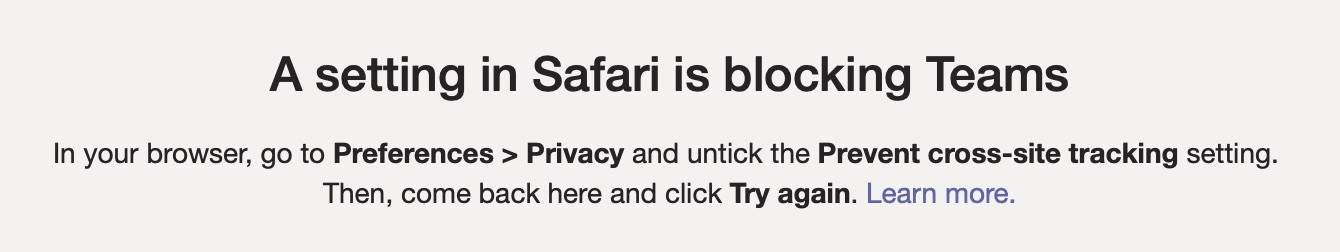

“A setting in Safari is blocking Teams. In your browser, go to Preferences > Privacy and untick the Prevent cross-site tracking setting.”

Umm… No.

Two nice screenshot features in macOS 10.15/iOS 13:

- screenshot on Mac can show up on another device (e.g. iPad with Pencil). Edits on iPad reflected in real time on Mac

- get two screenshots using CarPlay, one of iPhone, one of car screen!

🤯 Modelling data (not behaviour) has been a huge part of my development work recently.

John Schoeman just made my brain explode (in a good way) demonstrating how a sprinkle of functional programming can totally simplify data processing: youtu.be/toSedSFnz…

Just watched another good RailsConf 2019 talk: Scalabale Observability for Rails Applications by John Feminella

Some really helpful advice on what to observe, how often and why to make sure an application is actually doing what we expect.

I went looking for a simple cloud based development environment for a project my son is working on and found repl.it/languages…

We’ve only kicked the tires so far but we had an empty Rails app up and running in seconds, not hours!

Micro.blog continues to steadily improve! I really appreciate how quickly Manton turned around some small improvements I suggested on Slack.

I’m also enjoying Byword for Markdown editing on iPhone, iPad and Mac. Link insertion (with link on the clipboard) is particularly slick!

Graphiti and Leverage

Episode 40 of Remote Ruby was so thought-provoking I added it back to my podcast queue.

After listening to it again my previous thoughts on Graphiti (at the end of that post) still stand. But something else jumped out at me this time…

Lee speaks passionately about Graphiti and Vandal enabling product owners or “business people” (I cringe at the label “non-technical”) to essentially explore the schema and see the relationships between data, much like they already do in Excel (or Business Intelligence tools).

It brings to mind what I wrote last night about the many levels of abstraction between one line in my Rails app and the hundreds of thousands of CPU operations that result.

There’s a huge productivity benefit to me not having to know much about CPU instructions, assembly language, C, virtual machines or abstract syntax trees just to query a database from a Rails app.

Similarly, I think there could be a huge productivity benefit if business people could examine existing queries to understand how their app works or point out logic flaws to the developers… or modify an existing query to extract some data without having to wait for a new API endpoint or report to be developed… or write a new query to demonstrate a product requirement or a feature they would like added.

Just like good developers work hard to understand the business they are supporting, I wonder if Graphiti and Vandal could be the lever that helps good business people better understand the app the developers are building.

The more I learn about programming, the more I discover how “inefficient” it can be…

While debugging my Rails apps I’ve noticed a single line of my code might cause dozens or even hundreds of other lines of Ruby code in various Rails gems to be executed.

Lately I’ve been learning that each of those hundreds of lines of Ruby has to be tokenised, then the tokens parsed into AST nodes and then the AST nodes compiled into YARV instructions. Each line of Ruby requires in 5-10 YARV instructions.

YARV is written mostly in C so each YARV instruction usually results in multiple lines of C code being run.

Each line of C then needs to be converted to assembly code for the current processor architecture.

The assembly code then gets converted to machine code, the actual instructions the CPU executes.

All that from a single line in my Rails app!

N.B. The deeper down the stack we go, the less confident I am of the details. I’m happy to be corrected if you notice I’ve got anything majorly wrong but don’t let technical details distract you from the main point :)

There are so many layers of “inefficiency” from the code’s perspective!!! And yet, even with all that conversion and compilation and manipulation, the result is usually displayed pretty much instantly the moment I press enter in the Rails console or hit “go” in my browser.

Each of those layers is like a carefully machined gear, multiplying the power of the layers above. The result is that we can write clear and readable Ruby code, mostly oblivious to the mountain of code we’re relying on to do the actual work of updating a database, responding to an HTTP request or performing a complex calculation.

To me the key takeaway (other than being grateful for all that hard work) is that I shouldn’t worry about the “efficiency” of my Ruby code, especially not to begin with. The computer can deal with an extra line of code, one more variable or an additional method call. Instead I should focus entirely on making my code easy to read, easy to reason about and easy to refactor. I need to improve the efficiency of my coding as a whole, not my code.

I’m reading Ruby Under a Microscope (http://patshaughnessy.net/ruby-under-a-microscope) 📖

2.5 chapters in and I’m astounded by just how much effort must have gone in to building Ruby over the years!

I’m very grateful that I can freely benefit from all that work!!!

Parsing vs Evaluating Order

Following up from my Ruby pop quiz the other day, I asked about the surprising behaviour on Stack Overflow.

Some commenters provided a little bit of help and then I did some more research. An answer to my own question is below.

Jay’s answer to a similar question linked to a section of the docs where it is explained:

The local variable is created when the parser encounters the assignment, not when the assignment occurs

There is a deeper analysis of this in the Ruby Hacking Guide (no section links available, search or scroll to the “Local Variable Definitions” section):

By the way, it is defined when “it appears”, this means it is defined even though it was not assigned. The initial value of a defined [but not yet assigned] variable is nil.

That answers the initial question but not how to learn more.

Jay and simonwo both suggested Ruby Under a Microscope by Pat Shaughnessy which I am keen to read.

Additionally, the rest of the Ruby Hacking Guide covers a lot of detail and actually examines the underlying C code. The Objects and Parser chapters were particularly relevant to the original question about variable assignment (not so much the Variables and constants chapter, it simply refers you back to the Objects chapter).

I also found, to see how the parser works, a useful tool is the Parser gem. Once it is installed (gem install parser) you can start to examine different bits of code to see what the parser is doing with them.

That gem also bundles the ruby-parse utility which lets you examine the way Ruby parses different snippets of code. The -E and -L options are most interesting to us and the -e option is necessary if we just want to process a fragment of Ruby such as foo = 'bar'. For example:

> ruby-parse -E -e "foo = 'bar'"

foo = 'bar'

^~~ tIDENTIFIER "foo" expr_cmdarg [0 <= cond] [0 <= cmdarg]

foo = 'bar'

^ tEQL "=" expr_beg [0 <= cond] [0 <= cmdarg]

foo = 'bar'

^~~~~ tSTRING "bar" expr_end [0 <= cond] [0 <= cmdarg]

foo = 'bar'

^ false "$eof" expr_end [0 <= cond] [0 <= cmdarg]

(lvasgn :foo

(str "bar"))

ruby-parse -L -e "foo = 'bar'"

s(:lvasgn, :foo,

s(:str, "bar"))

foo = 'bar'

~~~ name

~ operator

~~~~~~~~~~~ expression

s(:str, "bar")

foo = 'bar'

~ end

~ begin

~~~~~ expression

Both of the references linked to at the top highlight an edge case. The Ruby docs used the example p a if a = 0.zero? whlie the Ruby Hacking Guide used an equivalent example p(lvar) if lvar = true, both of which raise a NameError.

Sidenote: Remember = means assign, == means compare. The if foo = true construct in the edge case tells Ruby to check if the expression foo = true evaluates to true. In other words, it assigns the value true to foo and then checks if the result of that assignment is true (it will be). That’s easily confused with the far more common if foo == true which simply checks whether foo compares equally to true. Because the two are so easily confused, Ruby will issue a warning if we use the assignment operator in a conditional: warning: found `= literal' in conditional, should be ==.

Using the ruby-parse utility let’s compare the original example, foo = 'bar' if false, with that edge case, foo if foo = true:

> ruby-parse -L -e "foo = 'bar' if false"

s(:if,

s(:false),

s(:lvasgn, :foo,

s(:str, "bar")), nil)

foo = 'bar' if false

~~ keyword

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ expression

s(:false)

foo = 'bar' if false

~~~~~ expression

s(:lvasgn, :foo,

s(:str, "bar"))

foo = 'bar' if false # Line 13

~~~ name # <-- `foo` is a name

~ operator

~~~~~~~~~~~ expression

s(:str, "bar")

foo = 'bar' if false

~ end

~ begin

~~~~~ expression

As you can see above on lines 13 and 14 of the output, in the original example foo is a name (that is, a variable).

> ruby-parse -L -e "foo if foo = true"

s(:if,

s(:lvasgn, :foo,

s(:true)),

s(:send, nil, :foo), nil)

foo if foo = true

~~ keyword

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ expression

s(:lvasgn, :foo,

s(:true))

foo if foo = true # Line 10

~~~ name # <-- `foo` is a name

~ operator

~~~~~~~~~~ expression

s(:true)

foo if foo = true

~~~~ expression

s(:send, nil, :foo)

foo if foo = true # Line 18

~~~ selector # <-- `foo` is a selector

~~~ expression

In the edge case example, the second foo is also a variable (lines 10 and 11), but when we look at lines 18 and 19 we see the first foo has been identified as a selector (that is, a method).

This shows that it is the parser that decides whether a thing is a method or a variable and that it parses the line in a different order to how it will later be evaluated.

When the parser runs:

- it first sees the whole line as a single expression

- it then breaks it up into two expressions separated by the

ifkeyword - the first expression

foostarts with a lower case letter so it must be a method or a variable. It isn’t an existing variable and it IS NOT followed by an assignment operator so the parser concludes it must be a method - the second expression

foo = trueis broken up as expression, operator, expression. Again, the expressionfooalso starts with a lower case letter so it must be a method or a variable. It isn’t an existing variable but it IS followed by an assignment operator so the parser knows to add it to the list of local variables.

Later when the evaluator runs:

- it will first assign

truetofoo - it will then execute the conditional and check whether the result of that assignment is true (in this case it is)

- it will then call the

foomethod (which will raise aNameError, unless we handle it withmethod_missing).

Some nice little refinements in the Apple ecosystem… macOS Catalina prompts you to join your Personal Hotspot when regular Wifi networks are unavailable… and if you say yes it asks if you want it to happen unprompted in the future.

Ruby Pop Quiz

if false

foo = 'bar'

end

foo

What will the result be?

a. foo

b. ‘bar’

c. NameError (undefined local variable or method `foo’ for main:Object)

d. ‘foo’

e. nil

f. None of the above

With my (admittedly limited) understanding of Ruby it was my intuition that the foo = 'bar' line would not get evaluated at all and therefore this would result in a NameError (option C).

I was surprised to learn that the result was actually nil. That is, the program knows foo exists but nothing is assigned to it.

With this new piece of information my intuition is now that the line is parsed but not evaluated (executed?). I’m guessing the process of parsing adds a foo node to the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) and the presence of foo in the AST prevents the NameError I previously expected.

Now I need to figure out how to confirm that hunch… and whether it’s a good use of my time to do so ¯_(ツ)_/¯

Testing Security Controls

I’m working my way through RailsConf 2019 and I keep finding gems (excuse the pun).

No Such Thing as a Secure Application by Lyle Mullican was one such gem.

Some highlights for me were:

On Automated tests

Learning to test made me write better code… When we start to think about writing security tests we design better security controls

[Even] if you’re not testing your security controls, somebody [else] probably is… and you really don’t want to outsource security testing to the Internet

On Static Analysis

If you get false positives from a static analysis tool it might be a code smell:

If I’ve made my code hard for Brakeman to understand and reason about then I’m probably making it too hard for people to understand as well

Resilience

How well do we react to failure:

- In our app?

- Segmenting

- Limiting fall out

- In our culture?

- Blame others? Head in sand?

- Or strive to iterate and improve the security system?

Other nuggets

- Combine unit testing, static analysis, dynamic tests and manual tests for Defence in Depth

- Exploits take time… a tripwire or automated black list might be worthwhile

Will Leinweber has a lot of experience with Postgres. His RailsConf talk on what to do When it all goes Wrong (with Postgres) was very informative. I’m keen to try and learn those tools before a problem occurs!

Really thoughtful guidance on Service Objects in Ruby: katafrakt.me/2018/07/0…

Keeping them “flat” is particularly helpful. I now realise I’ve written some convoluted ones recently that probably need functionality extracted.